The interest rate is a key input to pricing various instruments. For example, the price of an option depends on the risk free rate. The return earned holding bonds depends on the bond yield. A good model of interest rates means you can better price these interest rate derived products and have a better idea of risk.

The fiddly thing is that there is no one single interest rate. The yield that you can earn is dependent on how much time you are willing to wait. For example, you could put your money into a bank account for 1 day, you could buy a 3 month bond or even a 30 year bond. Each of these instruments will earn you a different yield.

These different time horizons with different yields are referred to as the yield curve. And this yield curve is changing over time. We can easily observe this by fetching data for US treasury yields from FRED. See the appendix for the time series used in this article. Have a look at the following chart that shows three different dates with different yield curves.

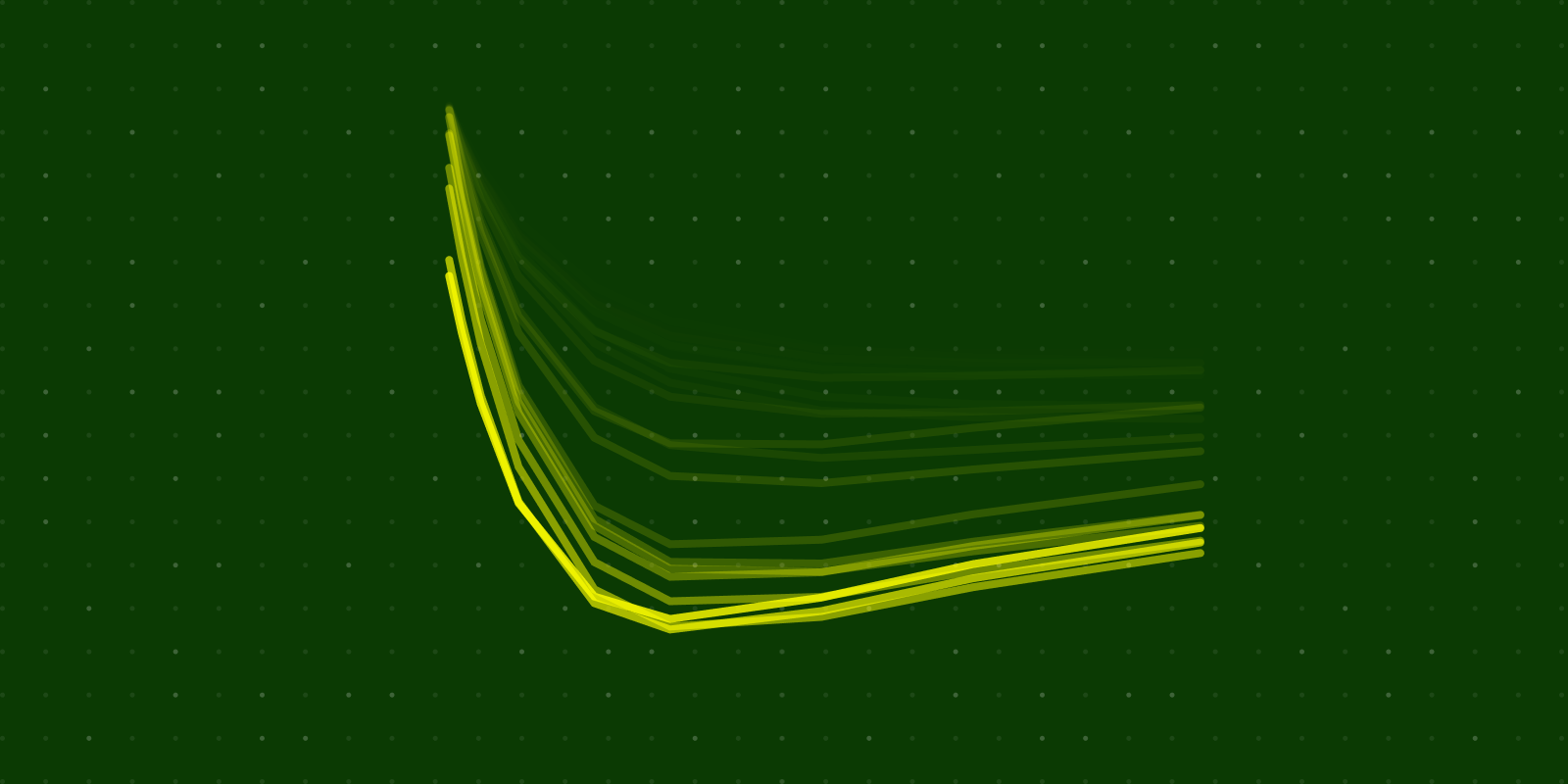

And over time, the yields have looked like this:

You can see periods of high yields and periods of low yields. You can see when investing in longer term bonds gives you a higher return and periods where investing in short term bonds gives you a higher return.

In this article, we’re going to learn how to model this yield curve over time with a factor model.

Factors

Have a close look at Figure 2, the chart showing the different yields over time. Notice how they’re all similar. They’re not all exactly the same, but they generally follow the same path. We could say that all these different yields have some common factors–they are related somehow.

The idea behind factors is that some series $x$ can be written as a linear combination of some number of factors plus an error term: $$ x_t = \beta_1 f_1 + \beta_2 f_2 + \dots + \beta_n f_n + e_t $$ The $f$ variables are called the factors and the $\beta$ variables are called the factor loadings.

These factors become extremely useful when you use the same factors to model a multivariate series: $$ \begin{align} \boldsymbol{x}_t = \boldsymbol{\beta}\boldsymbol{f}_t + \boldsymbol{e}_t \label{1} \tag{1} \end{align} $$

The most common way of investigating factors when you have a multivariate time series is to use Principle Component Analysis (PCA). The idea behind PCA is to find a set of completely uncorrelated time series to act as factors and the corresponding factor loadings. The factors found by PCA are called principle components, but we will continue to use the term factors. PCA is an old, robust and well studied algorithm. If you want to learn about it I recommend you read Principal Component Analysis which is a fantastic overview.

Running a PCA over the treasury yields confirms our intuition that there are common factors. I ran a PCA over the maturities 1 year or longer. The maturities shorter than a year have missing values. We can create a cumulative scree plot showing the percentage of variance explained by the first n factors. We see that 98.33% of the variance is explained by the first factor and 99.98% of the variance is explained by the first 3 factors.

Using PCA, we’ve found 3 factors that explains just about 100% of 8 treasury yields. These three factors do have some intuition behind them. Take a look:

The first factor looks like the long term yield from Figure 2. All the yields appear to mostly follow the long term rate (30 year yield) with larger deviations for shorter yields. These deviations must be captured in the other two components–they explain short term deviations in yield.

The real insight comes from looking at the factor loadings. Let’s see the factor loadings plotted against the time to maturity:

The first factor loading is virtually unchanged across the terms. This means that the first factor contributes the same amount for each yield. This makes sense as we’ve discovered that it represents the long term yield and explains over 98% of all the variance across all yields.

The second factor loading peaks for the shortest yields and then declines. We can interpret this factor as the short term yield.

The third factor loading peaks for more medium term yields. We can interpret this factor as the medium term yield.

Drawback of PCA

PCA has two drawback when used in practice. The first is that PCA requires clean time-series. For the yields that we are working on, there are gaps in the data. The most notable gap is that the 20 year yields start the early 60s but the 30 year yields do not start until the late 70s. And then, the 20 year yields stop for an extended period of time around 1990. The short term yields are missing enough samples that the PCA analysis performed above excluded them completely.

The second drawback is that we will need to calculate the PCA factors and factor loadings in a rolling window style fashion. This means that from point-in-time to point-in-time, the entire history of the factors are changing and the future of the factors might not be statistically similar to their point-in-time estimate.

The next section gets around PCA entirely.

Fundamental loadings

The factor loadings shown in Figure 5 appear smooth with respect to maturity. This suggests that we could model the factor loadings ($\beta$) as a function of maturity ($\tau$). Given such a function, we can rewrite equation $\eqref{1}$ as: $$ \boldsymbol{y}_t = \boldsymbol{\beta}\boldsymbol{f}_t + \boldsymbol{e}_t $$

expanding out the matrices:

$$ \left[ \begin{matrix} y_t(\tau_1) \\ y_t(\tau_2) \\ \vdots \\ y_t(\tau_n) \\ \end{matrix} \right] = \left[ \begin{matrix} \beta_1(\tau_1) & \beta_2(\tau_1) & \beta_3(\tau_1) \\ \beta_1(\tau_2) & \beta_2(\tau_2) & \beta_3(\tau_2) \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \\ \beta_1(\tau_n) & \beta_2(\tau_n) & \beta_3(\tau_n) \\ \end{matrix} \right] \left[\begin{matrix} f_{1,t} \\ f_{2,t} \\ f_{3,t} \\ \end{matrix}\right] + \left[\begin{matrix} e_{1,t} \\ e_{2,t} \\ \vdots \\ e_{n,t} \\ \end{matrix}\right] \label{2} \tag{2} $$

Where $\tau$ is the time to maturity, $y_t(\tau_n)$ is the yield to maturity $\tau_n$ at time $t$, $\beta_i(\tau_n)$ is a function for the $i$th factor loading for maturity $\tau_n$, $f_{i,t}$ is the $i$th factor at time $t$ and $\boldsymbol{e}_t$ is a vector of the error terms.

We solve for $\boldsymbol{f}_t$ with a cross-sectional regression. That is, at each time $t$ we would take the yields $\boldsymbol{y}_t$, the factor loadings $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ and regress the factors $\boldsymbol{f}_t$.

This method has the advantages that (1) if there are any yields missing at time $t$ they are simply excluded from the regression and (2) that the factor values at time $t$ do not depend on the historical values of the yields. This solves the two drawbacks of PCA.

Modelling the loadings

The paper by Diebold and Li present what they call the Nelson-Siegel yield curve 1: $$ y_t(\tau) = f_{1,t} + f_{2,t}\left(\frac{1 - e^{\lambda \tau}}{\lambda \tau}\right) + f_{3,t}\left(\frac{1 - e^{\lambda \tau}}{\lambda \tau} - e^{\lambda \tau}\right) $$ In their paper, they call this model the “Nelson-Siegel yield curve” as they base it on another paper. However, they do make some modifications of their own.

The equation says that the yield $y$ of maturity $\tau$ (in months) at time $t$ is a function of three factors ($f_{1,t}$, $f_{2,t}$ and $f_{3,t}$) weighted by the following factor loadings: $$ \begin{aligned} \beta_1(\tau) &= 1 \\ \beta_2(\tau) &= \frac{1 - e^{\lambda \tau}}{\lambda \tau} \\ \beta_3(\tau) &= \frac{1 - e^{\lambda \tau}}{\lambda \tau} - e^{\lambda \tau} \\ \end{aligned} $$

These three factor loadings look like this:

The parameter $\lambda$ control how quickly the curve decays to the right. When $\lambda$ is large the decay is fast providing a better fit for short term maturities. In the original Nelson-Siegel model, $\lambda$ varies with time. However, in Diebold and Li’s paper they note that $\lambda$ controls which maturity $\beta_3(\tau)$ reaches its maximum value. They fix $\lambda = 0.0609$ which corresponds to maximising $\beta_3(\tau)$ at a maturity of about 30 months.

A few facts on this model:

-

When the time to maturity is maximised ($\tau = \infty$) then $\beta_2(\infty) = 0$ and $\beta_3(\infty) = 0$ meaning that $y_t(\infty) = f_{1,t}$. This means that $f_{1,t}$ is the long-term factor which corresponds to what we noted in the PCA analysis.

-

The loading $\beta_2(\tau)$ starts at 1 for a maturity of 0 and decays to 0 as the maturity increases. This factor ($f_{t,2}$) can been seen as a short-term factor.

-

The loading $\beta_3(\tau)$ starts at 0 and ends at 0. Thus, $f_{t,3}$ is neither a short term nor long term factor. This is viewed as a medium-term factor.

-

The short term factor can be viewed as related to the yield curve slope; that is, the increase in yield from a short maturity to a long maturity. In fact, $y_t(\infty) - y_t(0) = -f_{t,2}$.

-

The instantaneous yield depends on both the long-term and short-term factors: $y_t(0) = f_{t,1} + f_{t,2}$.

Calculating factors

Now that we have functions for the factor loadings, we can take equation $\eqref{2}$ and at each time step $t$ do a cross-sectional regression of $\boldsymbol{\beta}\boldsymbol{f}_t = \boldsymbol{y}_t$. Giving us a time series of three factors.

We can reproduce Figure 1 and add in the fitted yield curve. The model captures the general shape of the yield curve:

Conclusion

We’ve seen that the US treasury yields across maturities contain common factors. A Principle Component Analysis (PCA) will show that 3 factors can explain nearly 100% of all the variance. We’ve created a model for the factor loadings so that these loadings are constant and known. Using these loadings, we can back out the three factors and get a pretty good model of yields.

Appendix

The following series were downloaded from FRED for the analysis in this article:

| Description | FRED Code | Link |

|---|---|---|

| 1 month yield | DGS1MO | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS1MO |

| 3 month yield | DGS3MO | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS3MO |

| 6 month yield | DGS6MO | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS6MO |

| 1 year yield | DGS1 | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS1 |

| 2 year yield | DGS2 | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS2 |

| 3 year yield | DGS3 | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS3 |

| 5 year yield | DGS5 | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS5 |

| 7 year yield | DGS7 | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS7 |

| 10 year yield | DGS10 | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS10 |

| 20 year yield | DGS20 | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS20 |

| 30 year yield | DGS30 | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS30 |