Fractional Brownian motion

Fractional Brownian motion is defined as a stochastic Gaussian process $X_t$ that starts at zero $X_0 = 0$ has an expectation of zero $\mathbb{E}[X_t] = 0$ and has the following covariance1: $$ \mathbb{E}[X_t X_s] = \sigma^2 \frac{1}{2}(|t|^{2H} + |s|^{2H} - |t - s|^{2H}) \label{1}\tag{1} $$ where $\sigma$ is the volatility parameter and $H \in (0, 1)$ is the Hurst exponent.

The Hurst parameter $ H $ controls the auto-correlation in the process. When $H = 0.5$ then you get regular Brownian motion — where the increments are an uncorrelated Gaussian process. When $H \lt 0.5$ then you get a process that is more mean reverting and when $H \gt 0.5$ you get a process that exhibits sustained trends.

Sometimes the mathematics behind stochastic processes can seem a little mystifying. Here’s an interactive example where you can play around with the Hurst exponent to see how the process changes.

The processes in the plot above were generated based on the method of taking the square root of the covariance matrix. The method is described on the Wikipedia page. The details for how to calculate the square root of the covariance matrix can be found in a previous article: Square root of a portfolio covariance matrix .

Intuitively, from playing with the Hurst exponent in the chart above, we can see that when $H \gt 0.5$ there are positive auto-correlations and when $H \lt 0.5$ there are negative auto-correlations. We can see this mathematically by reworking the covariance function into the covariance between increments2: $$ \mathbb{E}[(X_t - X_s)(X_v - X_u)] = \sigma^2 \frac{1}{2}(|u - t|^{2H} + |v - s|^{2H} - |v - t|^{2H} - |u - s|^{2H}) $$

If we’re looking at a h-step ahead covariance of a differenced time series, this would mean that: $$ \begin{aligned} s &= t - 1 \\ v &= t + h \\ u &= t + h - 1 \\ \end{aligned} $$ so the covariance function becomes: $$ \mathbb{E}[(X_t - X_{t - 1})(X_{t + h} - X_{t + h - 1})] = \sigma^2 \frac{1}{2}(|h - 1|^{2H} + |h + 1|^{2H} - 2|h|^{2H}) $$

We can see in the chart below that when $H \gt 0.5$ there are positive auto-correlations and when $H \lt 0.5$ there are negative auto-correlations.

Forecasting fractional Brownian motion

Let $\boldsymbol{p}_{t+1}$ be a vector of logged currency prices where the last value is the price one step into the future: $$ \boldsymbol{p}_{t+1} = \left[ \begin{matrix} \boldsymbol{p}_t \\ p_{t+1} \\ \end{matrix} \right ] $$

Modelling $\boldsymbol{p}_{t+1}$ as a fractional Brownian motion means that $\mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{p}_{t+1}] = 0$ and the covariance matrix follows equation $\ref{1}$. The covariance matrix is partitioned as: $$ \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{t+1} = \left[ \begin{matrix} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_t & \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{t,t+1} \\ \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{t,t+1}^T & \sigma^2_{t+1} \\ \end{matrix} \right ] $$

In the appendix I show how to calculate a conditional Gaussian distribution. We can calculated the expected value of $p_{t+1}$ conditioned on $\boldsymbol{p}_t$ as: $$ \mathbb{E}[p_{t+1} | \boldsymbol{p}_t] = \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{t,t+1}^T\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_t^{-1} \boldsymbol{p}_t $$

This is a linear combination of past prices. We can calculate the linear weights in Python with:

import numpy as np

def fbm_weights(window, H):

t = np.arange(1, window+1).reshape(-1, 1)

s = t.T

cov = 0.5 * (t**(2*H) + s**(2*H) - np.abs(t - s)**(2*H))

cov_v = 0.5 * (t**(2*H) + (window+1)**(2*H) - np.abs(t - (window+1))**(2*H))

weights = cov_v.T @ np.linalg.inv(cov)

return weights.flatten()

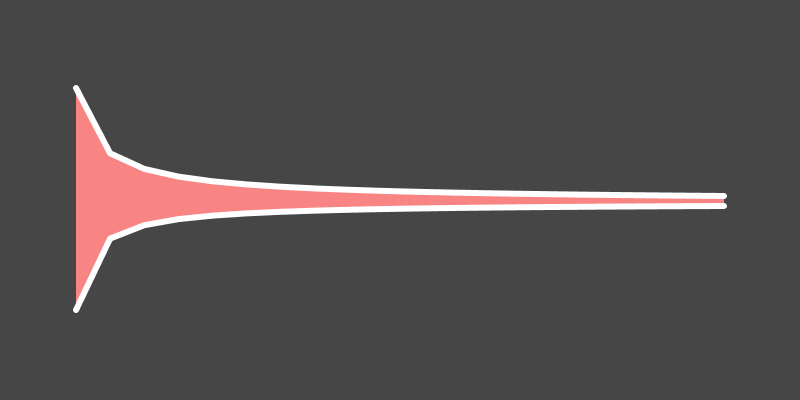

Using the parameters window = 30 and H = 0.45, the weights look like:

If we have a Pandas DataFrame of prices we can predict the next step ahead price with:

# prices = pandas.DataFrame of currency prices

weights = fbm_weights(window=100, H=0.45)

predicted_price = prices.rolling(100).apply(lambda x: weights @ x)

Forecasting currency returns

Taking the predicted_price DataFrame above, we can calculate the expected return for each currency with:

predicted_return = predicted_price / price - 1

I find that calculating mispricing yields a stronger signal than predicting returns. In this context, if we predict that a currency is expected to return 1% but it actually returns 2%, then we say that the currency is 1% mispriced and we expect it to move lower by 1%.

We can calculate this mispricing with:

actual_returns = prices.pct_change()

mispricing = predicted_return.shift(1) - actual_returns

The mispricing DataFrame will contain positive values for currencies that we believe are undervalued and negative values for currencies we believe are overvalued.

We can then normalise these mispricings so that currencies with a higher mispricing have a greater weight in our portfolio. We normalise so that absolute sum of the portfolio weights equals 1:

portfolio_weights = mispricing.divide(mispricing.abs().sum(1), axis=0)

We can get an idea of the strength of this signal by looking at an equity curve without transaction costs:

portfolio_returns = (actual_returns * portfolio_weights.shift(1)).sum(1)

capital = (1 + portfolio_returns).cumprod()

As an example, I use a dataset (the prices DataFrame) of 30 minute prices of the following pairs:

CAD_USD

EUR_USD

JPY_USD

SEK_USD

GBP_USD

SGD_USD

PLN_USD

CHF_USD

AUD_USD

NOK_USD

CZK_USD

NZD_USD

DKK_USD

CNH_USD

HUF_USD

which are most of the currencies on Oanda except for HKD which is pegged to the USD and some of the less traded currencies.

Calculating capital on this dataset gives me:

This is a fairly basic model, all we’ve done is derive a linear filter of past prices. Yet, there appears to be a fair amount of predictive power. The problem is that if I were to include transaction costs, all performance disappears. This predictive signal isn’t strong enough to overcome transaction costs and is more suitable as a feature in a machine learning model.

Summary

Here we’ve made a linear filter of past prices that predicts future returns derived from the fractional Brownian motion stochastic process. This filter demonstrates predictive power, however, not enough to overcome transaction costs. Specifically, the signal does not overcome the spread.

Appendix

Conditional Gaussian distribution

Define $\boldsymbol{x}$ to be a $d$ dimensional Gaussian vector: $$ \boldsymbol{x} \in \mathcal{R}^d \sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{\mu}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}) $$

Partition $\boldsymbol{x}$ into two disjoint sets $a$ and $b$: $$ \boldsymbol{x} = \left[\begin{matrix} \boldsymbol{x}_a \\ \boldsymbol{x}_b \\ \end{matrix} \right ] $$ and also split the mean vector $\boldsymbol{\mu}$ and covariance matrix $\boldsymbol{\Sigma}$ into corresponding partitions: $$ \boldsymbol{\mu} = \left[ \begin{matrix} \boldsymbol{\mu}_a \\ \boldsymbol{\mu}_b \\ \end{matrix} \right ] \quad \boldsymbol{\Sigma} = \left[ \begin{matrix} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{aa} & \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{ab} \\ \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{ba} & \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{bb} \\ \end{matrix} \right ] $$ Note that because $\boldsymbol{\Sigma}$ is symmetric that means that $\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{aa}$ and $\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{bb}$ are symmetric and that $\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{ab} = \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{ba}^T$.

The distribution of $\boldsymbol{x}_a$ conditional on $\boldsymbol{x}_b$ is: $$ \boldsymbol{x}_a | \boldsymbol{x}_b \sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{\mu}_{a|b}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{a|b}) $$ where: $$ \begin{aligned} \boldsymbol{\mu}_{a|b} &= \boldsymbol{\mu}_a + \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{ab}\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{bb}^{-1} (\boldsymbol{x}_b - \boldsymbol{\mu}_b) \\ \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{a|b} &= \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{aa} - \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{ab}\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{bb}^{-1}\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{ba} \end{aligned} $$

For the curious, you can find a derivation of the Gaussian conditional distribution in section 2.3 of 3. I found a PDF online of this section.